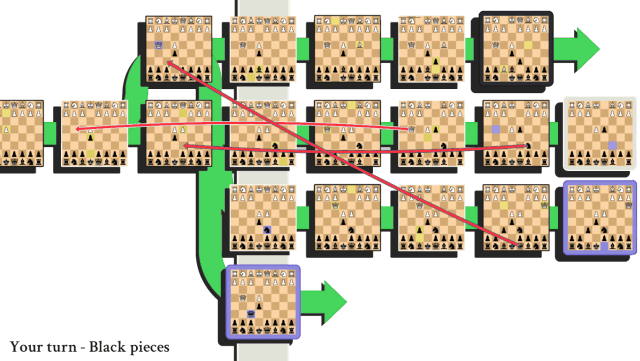

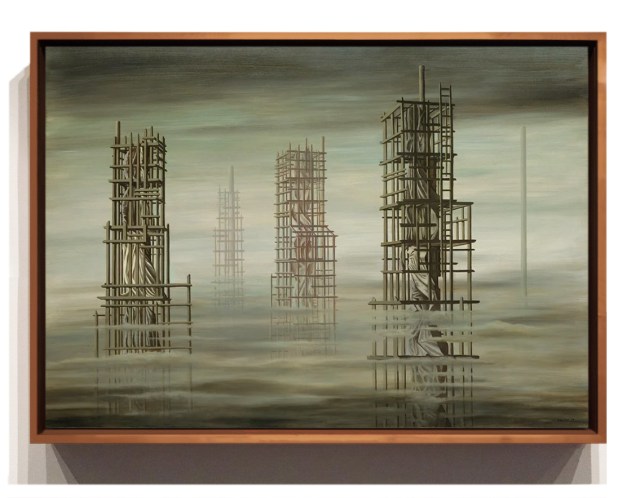

Such personal correspondence and diaries as survive suggest that social relations from the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries tended to be cool, even unfriendly. The extraordinary amount of casual interpersonal physical and verbal violence, as recorded in legal and other records, shows clearly that at all levels men and women were extremely short-tempered. The most trivial disagreements tended to lead rapidly to blows, and most people carried a potential weapon, if only a knife to cut their meat. As a result, the law courts were clogged with cases of assault and battery. The correspondence of the day was filled with accounts of brutal assault at the dinner-table or in taverns, often leading to death. Among the upper classes, duelling, which spread to England in the late sixteenth century, was kept more or less in check by the joint pressure of the Puritans and the King before 1640, but became a serious social menace after the Restoration. Friends and acquaintances felt honour bound to challenge and kill each other for the slightest affront, however unintentional or spoken in the careless heat of passion or drink. Casual violence from strangers was also a daily threat. Brutal and unprovoked assaults by gangs of idle youths from respectable families, such as the Mohawks, were a frequent occurrence in eighteenth-century London streets; and the first thing young John Knyveton was advised to do when he came to the fashionable western suburb of London in 1750 was to buy himself a cudgel or a small sword and to carry it for self-defence, especially after dark.

—Lawrence Stone: The Family, Sex and Marriage in England, 1500-1800 (1977)

Image:

Theodoor Rombouts: Card and Backgammon Players Fight over Cards (1620-1629)

![Turin Strike Papyrus [Cat. 1880]](https://corvusfugit.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/turin-strike-papyrus-cat.-1880.jpg?w=640)